- HOME ›

- Speech delivery ›

- Importance of eye contact

Why is eye contact important?

5 activities for teaching good eye contact

By: Susan Dugdale

Eye contact, or the lack of it, in Western culture, plays a vital role in all our face-to-face communication.

To communicate well we need to be able to look people in the eye while either speaking or listening, as this shows we are actively involved the interaction - present and interested.

But how do you teach that to students in an effective, non-threatening, fun way? And why is eye contact so important and, what does it actually mean?

Here's five proven eye contact focused activities that will work well from middle school upwards, along with additional information on cultural difference, the meaning of eye contact, why it can be difficult make, and more.

Use the jump links below to move around this long page easily.

What's on this page

Activities to teach eye contact (with extensions) suitable for middle school and up

- Don't you dare look into that person's eyes

- Talking complete hogwash, piffle, total bumkin

- I'm talking to you, and you, and you, and you

- One phrase, or one thought, to one person

- When good looks go bad

Information about eye contact: why it is important and more

- Good versus creepy eye contact

- The sweep and other eye contact patterns public speakers and presenters sometimes use

- The secondary skills needed to support great eye contact

- Cultural difference and eye contact

- The meaning of eye contact - how it is interpreted

- Why is eye contact so important? - the reasons

- Why is it so difficult to make eye contact?

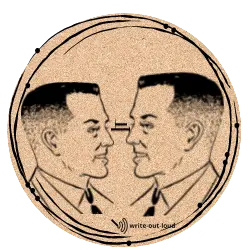

Definition of 'eye contact'

noun

the situation in which two people look at each other's eyes at the same time:

Here's two example sentences using the phrase 'eye contact'. The first sentence lets us know more about the person being spoken about and the second sentence tells us more about the person being spoken to. Both of them reflect Western cultural beliefs about eye contact.

- He's very shy and never makes eye contact.

- If you're telling the truth, why are you avoiding eye contact with me?

Definition from:

https://dictionary.cambridge.org/dictionary/english/eye-contact

Activities to teach eye contact

I taught teenagers. These are wonderful, dynamic, exacting people who can lurch wildly between, "Yes, I can. Yes, I will. Yes, I'm doing it! Watch me now!" and complete abject misery.

"I can't! I won't! I'll die if you make me give a speech. And if you try and make me, make eye contact while I'm up there, in front of others, publicly dying, you're the cruelest most heartless woman in the world."

If you've taught the age group, you'll know.

So here are the activities I used with classes to get them comfortable with making eye contact while delivering a speech. I've found they work well with adults too.

The rationale behind them is simple. If we tease apart the skills we bundle together as public speaking confidence, it makes teaching and practicing them easier and more effective.

Making good eye to eye contact is one of these skills. Just as using appropriate language is, or standing tall, speaking clearly, providing suitable handouts are...and so on.

Once isolated a skill can be taught and learned. Then, hopefully, it can be easily used without conscious effort.

It's a strategy that worked for me. I hope it does for your students too. Take it slowly. Make it fun, and give them lots of encouragement.

What's needed to do these activities

You'll need:

- a large room, big enough to split your class into separate groups, and one where the sound of lots of people talking at once is not going to disturb people in classrooms nearby

- a stopwatch or timer

1. Don't you dare look into that person's eyes!

One of the ways I found to successfully break down fear of public speaking was to encourage students to consciously exaggerate public speaking 'faults' until they became utterly ludicrous, and hilariously funny. (I made a game of it called Permission to Present Badly.) This activity is based on that.

After you've given the instructions they'll all work at the same time. Hence the comment about noise!

Working simultaneously provides enough security and privacy for shy kids to give the exercise a go. They would wither under the scrutiny of having to stand and deliver in front of the class by themselves! If everybody is behaving daftly, then they're not going to stand out.

Instructions

Split your class into pairs.

One person is the speaker. The other is the listener.

The speaker is to talk nonsense to the listener for 30 seconds. BUT they must NOT look into their eyes, at all. They can look over their shoulder, at the floor, the ceiling, a picture on the wall, to either side of them, anywhere as long as it's not into their eyes.

The nonsense could be the repetition of 'blah, blah, blah ...'

It could be tongue twisters. Choose one or two to say slowly, quickly, seriously, sadly ..., or however they want!

It might an exaggerated tale about how they got to school this morning.

"I took the flying ship this morning rather than ride my bike. Bikes are so ordinary and I wanted a change from the mundane. When Captain Marvel swung by to say there was a spare seat, and ask if I wanted it, I almost choked on my cereal. Yes, I said. YES!"

Or the most boring activity in the world. (If you want easy instant topic suggestions try these: 150 1 minute topic ideas)

The content doesn't matter. Stringing together something coherent is not the purpose. What is, is experiencing what is happening.

Encourage big, bold, unequivocal body language! The bigger, the betterer! You want HUGE exaggerated gestures.

While the speaker is avoiding the listener's eyes, the listener's task is to notice what that makes them feel like.

Call time when 30 seconds is up. Then swap roles and repeat.

Now pick a new partner and do the exercise once again. When both people have had a turn listening and speaking bring everyone together again.

Now the listener will not look at the speaker

Explain that they're going to do the complete exercise twice more with new partners, people they've not worked with previously.

However this time round, the listener is not going to attempt to make eye contact with the talker. They are going to deliberately not look.

They'll look away, at the floor, across the room ...anywhere except at the speaker's face and eyes. The speaker is going to try and make eye contact.

Swap over the roles and repeat.

Change partners and do the whole exercise again.

What's most likely to happen is great guffaws of laughter, and helpless giggles.

When it's done, pull everyone together for a feedback round. Cover what not being looked at felt like from both sides.

Give the best of the worst awards!

Lastly, ask if there were any stand out performances at the being the worst avoiders of people's eyes ever. Bring one or two of those couples out to the front for a demonstration. Award them Oscars. Clap, cheer and congratulate them on their fine effort.

Yes, it's nonsense. It's also fun, and very effective!

2.Talking complete hogwash, piffle, total bumkin

Divide your class/group into pairs.

They are going to stand opposite each other and take turns to look each other in the eye while again, spouting nonsense for 30 seconds.

To keep it simple use the same material from the previous exercise: repetitions of 'blah, blah, blah', tongue twisters, a daft story ...

Again, the content doesn't matter. What does, is getting accustomed to looking into people's eyes while speaking.

Once both people have had a turn to speak, get them to choose a new partner and repeat the exercise. Then do it once more.

When three rounds have been completed pull the group together for a quick feedback session.

What did they notice? How did it feel to listen and look? How did it feel to speak and look?

Go from pairs to groups of four

Now take it up a notch.

Split your class into groups of four.

Each person will take a turn to speak to an audience of three.

Keep the timing and the instruction to make eye contact the same. This time the speaker needs to spread it as equally as they can between the members of their audience.

When everyone has had a turn speaking bring everyone back for another quickfire feedback round. What happened? How did it feel? What worked? What didn't? What will you try next time?

Extension activities

Over the next few lessons increase the group size incrementally (8,10,15,20), until you have your students confidently standing to speak* in front of their entire class.

And then, if you have a hall with a stage available to you, use it. Put the speakers on the stage to have them get used to making eye contact from there.

*Please don't be tempted to change what they're speaking about to something they need to consider carefully, or even prepare. This exercise works because they don't have to think! All the focus needs to be on learning to feel OK with making good eye contact.

3. I'm talking to you, and you, and you, and you

This exercise is great to help your students practice spreading their eye contact evenly while speaking to a group of five and more.

(It's a precursor to teaching how to create the impression or illusion of holding a one to one conversation whilst speaking to a large group or an even bigger audience.)

Break your class into groups.

Arrange the seating of the groups so that they are separate and each is a distinct audience. Eg. two people in the front row, three in the back. If the group is larger; four people in the front, six at the back.

Nominate who is the first speaker, the second, the third, fourth etc.

Use a stop watch to monitor the time.

Give each group a list topic. Ideally it should be something very simple that doesn't require a great deal of thought. For example: the months of year, days of the week, counting numbers over 100, types of cars, local street names, vegetables, sports, the names of countries ...

Encourage smiling while speaking, nodding, or a pause before continuing.

The first speaker stands comes to the front of their group. They will talk for 30 seconds and every item on the list they say must directed to a particular person, and eye contact made with that person as they're speaking.

If the list is months of year, then 'January' is said while looking into the eyes of the person on their right in the front row. 'February' goes to the person directly in front of them in the back row. 'March' is for the person on their left in the front row, 'April' is given to person on their right in back row, and so on.

At the end of 30 seconds, call stop. The first speaker sits down in the audience.

The second speaker comes to the front. The timer is set for another 30 seconds.

On 'Go', they pick up the same list and continue. Eg. 'May' is said to the person at the back to their right. 'June' goes to the person right in front of them etc.

Run through until everybody has had a turn being the speaker.

Bring everyone back together for a feedback round to share what was learned.

I'm talking to you, & you, & you extensions

Variations on the basic activity include:

- increasing the group sizes

- having your students play with the delivery of words they say.

For instance, be ultra serious, excited, sad, irritated, or sulky.

How the words are said will change the experience for both the speaker and their receivers. - running it as a whole class.

Give each of your students a number. Choose a list, for example, vegetables. Next nominate a student to be speaker by calling a number, for example 17.

The student whose number is 17 comes to the front. The timer is set for 30 seconds, and on 'Go', they begin.

'Potatoes' to the right front. 'Lettuces' to the back left. 'Parsnips' to the center of the middle row etc.

Call 'Stop' when the 30 seconds is up. Call a new number to bring the next speaker to the front. Reset the timer. Call 'Go' and start again with the new person. 'Radishes' to back right ... and so on.

To ring in the changes, up the tempo, or slow it down, and swap the list topic for a new one.

3. One phrase, or one thought, to one person

This is an advanced extension of the previous exercise. The idea behind it is the same. The speaker will make eye contact with members of the audience while speaking.

However, instead of the contact being held while a single word is spoken, it's lengthened to the time it takes to deliver a phrase or one thought.

The optimum period of time to hold the contact is between 3 and 5 seconds.*

Get your students to make up a very simple speech. They'll use it in the exercise. It doesn't have to be true. ☺

Here's a couple of examples:

- "My name is Alfred McDonnegal.

I train big cats, lions and tigers, for circuses. Despite what some people say, my work is entirely ethical. I am looking forward to telling you more about it today." - "My name is Helen Smith.

I go to Westerbrook Highschool, sometimes reluctantly, sometimes happily. I've lived in this area all my life, as have my father's family. We go back five generations on his side."

Split your class into groups of five or six. Sort out the speaking order. (Everybody is to have a turn.) Arrange the seating so you have, an albeit small, front and back row.

Get your students to play with the delivery of their speeches, spreading their eye contact evenly around their audience.

For example "My name is Helen Smith" could go to the person in the middle of the back row.

"I go to Westerbrook Highschool," goes to the person in the front to the right of the speaker.

"sometimes reluctantly, sometimes happily". is delivered to the person in the front to the left of the speaker.

"I've lived in this area all my life," is said to the person in the back row on the right.

"as have my father's family." is said to the person in the back row on the left.

The last sentence, "We go back five generations on his side.", is delivered to the person in the middle of the back row.

Once everybody has had a turn being the speaker, bring the class together for a feedback round.

*Science Reveals the Right Timing for Eye Contact: New scientific study defines 'normal' eye contact for the first time (2016)

Good versus creepy eye contact

When does eye contact stop being good and start becoming uncomfortable or creepy? The study cited in the article I linked to above found 5 seconds was at the upper end of acceptable contact.

Depending on circumstances, anything more became intrusive, invasive and unwanted. It was staring, rather than looking. And, as my mother repeatedly told me when I was a child, staring is rude!

5. When good looks go bad

If you want to underline the need for people to monitor the length of their eye contact try this simple exercise.

Ask your class to walk randomly around the classroom. After about 20 seconds call "Stop".

Tell them pair up with the person closest to them. They are to stand facing each other about an arm's length apart.

Now they must look into each other's eyes without breaking away, or speaking, as you count slowly to 10.

Ask them to remember the number you had got to when the eye contact became uncomfortable.

Repeat the cycle of walking, calling "Stop", and staring while you count several times. Then do a feedback round.

The sweep and other eye contact patterns

Presenters using any rigidly adhered to predetermined or formulaic pattern for making eye contact will appear false to an audience.

For instance, some people use a sweep gesture. They'll turn their head to the side and begin a long slow sweep to the other side while scanning the audience.

Then there's a return journey doing the same thing. And it happens again, and again, from side to side, until the speech is finished.

This is not making eye contact. It's looking without seeing, speaking without connecting, and it doesn't work.

Neither does doing the equivalent of rushing frantically around. That is giving as many people as you can a quick glance when you come up to grab a breath before diving back, head down, to read aloud from your notes.

To be meaningful the eye contact must be mutual and sustained, as well as evenly spread throughout an audience.

In essence, it's akin to having multiple individual conversations, three to five seconds long, over the course of your presentation: one with the person in the middle of the third row in the middle section of your audience, another with the person at the end of the second row in the front section stage right, followed by one with the person in the back row of the back section stage left ...etc.

Secondary skills to support great eye contact

It's all very well saying a person should use as much eye contact as possible while giving a presentation or delivering a speech. It's easily done if you have a simple speech to make.

But how do you do it if you have a lengthy and complex presentation to give? Perhaps one involving power point slides?

The answer is to practice, a lot.

The skills you'll need to work on are:

- making and using cue or note cards

- reading aloud

- using a podium or lectern

- integrating any technology/props you intend to use into the flow of your presentation

- as well as, body language and using your voice effectively.

Click the link to find detailed notes covering: how to rehearse. These take you through what is required step by step. If you want to make giving a polished presentation appear effortlessly easy, it will take repeated practice.

Cultural difference and eye contact

Be wary of assuming what is right for you is also right for whomever you are speaking to. It doesn't work like that.

There are major differences across cultures. Seeking and expecting eye contact to be returned can be interpreted in many ways.

Depending on the cultural background of the audience a speaker actively making eye contact may be seen as:

- friendly,

- confident,

- competent,

- authoritative,

- respectful,

- hostile,

- giving an inappropriate invitation to flirt or more,

- ignorant (lacking understanding of correct social etiquette),

- or, arrogant.

Ask ahead of time if don't know what is regarded as fitting.

This 2018 article provides a good overview: 10 Places Where Eye-Contact Is Not Recommended (10 Places Where The Locals Are Friendly)

The meaning of eye contact

In the Western world the ability to make and sustain eye contact with whoever you are talking to is vitally important.

We attribute those who use it well as being:

- more trustworthy, honest and sincere

- more confident, capable and competent

- more likeable, personable and open

- more knowledgeable and skilled

We admire these people. They are more attractive to us, and more likely to be our leaders.

Good eye contact opens hearts and minds and, therefore, doors. Our lives are better in every way when we learn to look and be seen 'eye to eye'.

Why is eye contact so important?

The impact of using good eye contact is profound, but why? What makes it work so effectively?

There are several possible reasons.

1. Our eyes help us cooperate with each other

Our eyes have evolved the way they have to enable us to cooperate with each more efficiently. This is called the cooperative hypothesis. Researchers* studying it say that: "the distinctive features that help highlight our eyes evolved partly to help us follow each others' gazes when communicating or when cooperating with one another on tasks requiring close contact."

* For more see Live Science: Why Eyes Are So Alluring

2. Our eyes reflect what we truly think & feel

Consider all those common expressions referencing eyes. Here's a few:

- to be the apple of someone's eye, a feast for sore eyes, or easy on the eye

- to have a roving eye, eyes out on stalks, or eyes in the back of your head

- to do it with your eyes shut, without batting an eye, or to turn a blind eye

We can be starry eyed, dewy eyed, bright eyed, eagle, evil, green, black and red eyed. Our eyes can glaze over. Or we can be dead behind them.

Eyes have long been regarded as mirrors of the soul because they reveal what we are truly thinking and feeling.

As a baby we learned to scan and read our parents' faces, particularly their eyes, to figure out what was happening. It's a skill we've been using and refining ever since.

Eyeball to eyeball communication is instant, simultaneous and bypasses the need for words. It can take place anywhere and between people who neither speak nor understand each other's language.

3. Eye contact shows attention

To be in eye contact, to have someone's eyes meeting yours, is to be the focus of their attention. And being the center of undivided attention while you're talking with someone is a powerful affirmation, reinforcing our sense of self-worth.

It feels good to be acknowledged and to see and hear it in your listener's responses: their nodding, smiling, ahs, mms and yeahs.

The flip side is not being given meaningful eye contact while you're talking with someone. It doesn't feel good.

You know you're not being listened to properly because you can see their eyes flicking past you to look at another person, the phone in their hands, or out the window.

The unspoken message you're getting is, you and what you're saying is unimportant, not worthy of my notice.

4. Eye contact creates & nurtures connection

When we meet eye to eye, face to face, we are far less likely to fall out with each other. That is because when we look into each others eyes we see and feel our mutual humanity. We connect, and through connection we begin to understand each other. We become less likely to judge or behave hastily in any way.

In complete contrast, the internet allows us to interact without ever seeing who we are talking to. That anonymity is, unfortunately, enough to encourage keyboard warriors and trolls to bring out their worst. These are the people who deliberately write divisive, abusive, offensive, provocative or aggressive posts. They say things they would seldom, or never, say to a person if they met them face to face and could look them in the eye.

Why is it so difficult to make eye contact?

Because while we are seeing others as they really are, they are also seeing us. And being seen can make us feel very vulnerable. We may not welcome that for a number of reasons.

Maybe it's because we feel insecure about ourselves and our worth. Eye to eye contact will reveal that, so we'll dodge it. We'll look away, or down, particularly if a person whom we think has a much higher status than our own, is talking to us.

Perhaps it's because we've betrayed someone's trust and feel ashamed. Looking that person directly in the eyes is likely to reveal the truth, therefore we'll avoid the contact.

Another possibility is that we're trying to mask or hide what we genuinely think or feel in response to what the person is talking to us about. Perhaps we are trying to protect either ourselves, or them, in some way? We don't want our anger, disgust, jealousy, disappointment, disinterest ... to be seen.

Or the reluctance could be down to our cultural heritage.

In Western cultures, the more comfortable we feel about ourselves, (who we are, frailties and all) the more comfortable we about people seeing us. The habitual inability to look people in the eyes can be indicative of a person feeling ashamed of themselves. They fear others will discover how unworthy they really are.

A good reference for more information

Why meeting another’s gaze is so powerful BBC 2019

About the Author: Susan Dugdale, founder of write-out-loud.com, is a qualified teacher of English and drama with over 40 years of experience. Drawing on her professional expertise and her personal journey from shyness to confidence, Susan creates practical, real-world resources to help people find their voice and speak with power.