- HOME ›

- Speech delivery ›

- Characterization techniques for storytelling

Characterization techniques for

effective storytelling in speeches

Exercises for compelling body language and vocal variety

By: Susan Dugdale

If you've listened to and/or seen a good storyteller at work, you'll know 'becoming' the characters in your tale is vitally important for making them appear real and believable.

How do they do that?

They use varying characterization techniques, like the ones I've outlined below. These make all the difference between telling a story passively or actively.

When you're active, when you take on the attributes of a character, and the qualities of your story, you give your audience an opportunity to see, hear, and feel more clearly whatever it is you want them to.

If you're telling a tale in which a character talks angrily, they'll see anger in the way you use your body and hear it in your voice. This is "show AND tell".

And show and tell makes for compulsive, hang-off-every-word, ooh-aaah listening. That's powerful magic!

Page quick links

- What you need to know about characterization - the basics

- Beginning exercises for physical work - Mirror, mirror - Crossing the line

- Characterization techniques for voice

- Integrating characterization into your story

- Using illusion - how to work with multiple characters

Let's begin!

Most stories have, as well as a narrator, characters who talk and interact. Even if they are small 30 second tales they will still have some form of those elements.

The key to successfully telling a story, regardless of its size, is establishing credibility instantly. You do that using characterization techniques.

In my storytelling page I said if you are talking about a character being happy, sad, angry, jealous, shy etc, the way to make that believable was to "be" it.

Mastering basic characterization techniques ...

... means you need to know:

- What emotions do to body language and voice and,

- How to drop into, and out of those, emotive states very quickly to follow the flow of your story line.

Matching mood and body language

It's easier to begin with if you focus on your own body.

You're going to become aware and know what you do when you're experiencing differing emotions like being excited, ashamed, or confused.

For example:

Do you scrunch your forehead and tilt your head to one side when you're unable to understand what's going on?

Do you bounce on your toes when you're excited?

A quick way of getting this awareness is to remember times when you experienced those emotions, and to do the following exercise.

Mirror, mirror, on the wall ...

Decide on the emotion you want to replicate.

Now put yourself back into the situation where you felt that emotion.

Once you think you've captured the state accurately, hold it. Consciously 'freeze' in position - just like a statue, and look closely at what your body is doing to express it in the mirror.

Commit yourself to act - the bigger, the better!

The trick to getting the most out this exercise is to do it wholeheartedly. Without reservation. No holding back! Feel free to exaggerate. Make your movement as big as you can.

This is practice. You can do what you like. Don't worry about feeling foolish or silly. Nobody, aside from you, is watching!

This is not film

Remember small or subtle changes won't communicate rapidly to an audience. Lifting an eyebrow ironically a whole quarter of an inch is likely to be missed.

This is not film. You don't have the benefit of close-ups or long lingering shots.

You need to convey the mood immediately and unambiguously. To do that you need large, clean, clear movements. A flurry of indecisive gestures won't do it.

Practice changing from one feeling state to another

Once you've established what one mood feels like; where it is centered in your body, what it does to your posture, how it reflects on your face, change it for another.

Shift between two opposite emotions, like 'happy' to 'sad', 'angry' to 'fearful', 'pleased' to 'disappointed', 'anxious' to confident', so the differences between them are easily observed and remembered.

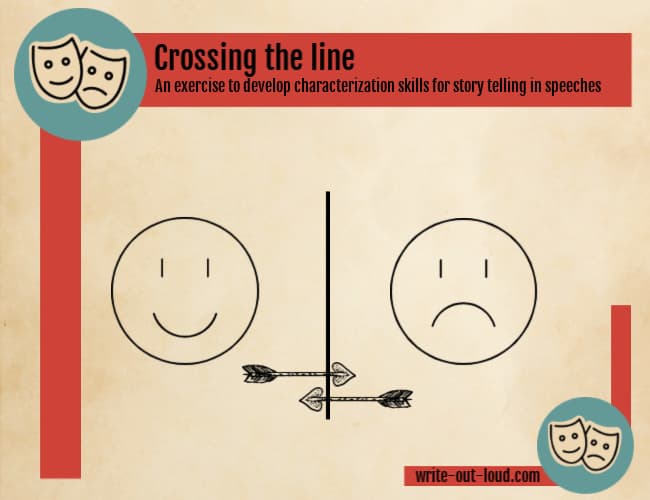

Crossing the line

The next step is to practice shifting states rapidly.

A technique I've used successfully in classes, which you can easily use in any space, is to draw a line on the floor.

One side of the line, for example, is 'happy' and the other 'sad'. I have students walk toward it holding 'happy' body language and immediately they step over it they must assume 'sad'.

We do this with 'angry' to 'fearful', 'shy' to 'confident', and so on, starting slowly and building up speed until the changes occur almost instantly.

As I said in the notes for the 'Mirror' exercise do not worry about being subtle at this point. You can refine what you do later.

It is enough for now that you consciously experience and are able to replicate the larger, bigger movements characterizing a particular emotional state. That is what will enable to flick in and out of them with ease.

And now let's move to ...

Characterization for voice

You'll be aware that tone, pitch, volume, and the speaking rate of words changes according to how we feel. That's one of the first things we learn as children.

For example, if the person closest to us, usually our mother, is angry then the volume of her voice is likely to be raised, as is the pitch. Her tone will be harsher and the rate the words fly out of her mouth may be much faster than usual.

Our task now is to figure out how to accurately and quickly characterize mood shifts with our voice.

- Do we need to alter pitch, tone or rate of speech?

- Do we need to stress some words or parts of them more than others?

- Do we need to hold some words up, or pause before saying them?

- And what breathing patterns do we need to underpin their delivery?

Begin with the body

A simple way of getting into the voice of a character is to begin with the body. Assume, or take on, the emotion first. Feel it through your entire body. And then add voice.

For example:

My character is tired and bored. I show that by slumping my shoulders forward. I let my center of gravity slip so my weight is mostly being carried through my legs. My arms may hang loose at my sides. My head is heavy on my neck and my face says, 'Yeah, so what!' I sigh heavily.

Then add voice

Now speak.

While holding the body language of your bored tired character say whatever comes first into your mind.

Listen carefully.

You're trying to hear if the emotion of your body (bored and tired) carries through to your voice.

It should sound 'flattish' and slightly held back as if speaking was an effort. If there are inflections they will tend to fall rather than rise.

Once you've heard and passed yourself as reasonably accurate for one mood - swap to another.

Keep using the mirror, or if you can, video yourself, noting the differences as you go so you can easily return and replicate what you've done.

Integrating characterization techniques into a story

To use these techniques effectively into your story, we need to refine them a little more.

Who is talking?

So far we've looked at mood and how mood informs body and then voice.

Now we need to look at 'who' the person is experiencing the mood and doing the talking.

- Is this person old, young, male, female, rich, poor etc, etc.?

- What physical mannerisms (stance, habit, way of talking) distinguishes them from anybody else?

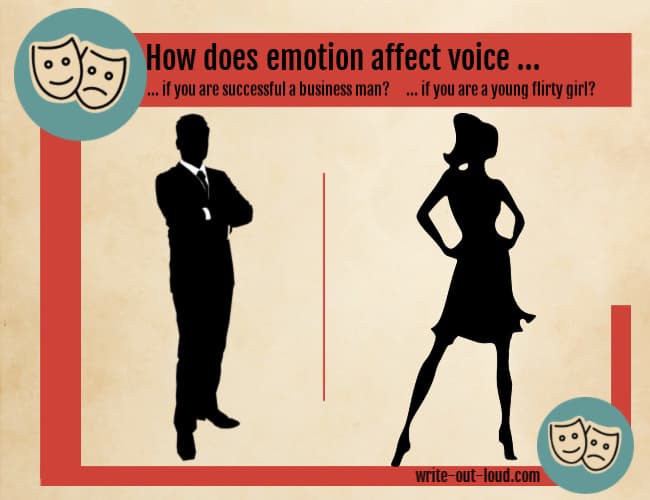

Use simple recognizable stereotypes

Characterization doesn't need to be complicated - simple is better. Try thinking stereotypes rather than 'real' people.

You need an easily identifiable gesture or body stance marking one character from another.

For example:

The successful business man, (left), impressed with his own power, quite literally stands as if he were full of himself. Feet apart, arms folded, chest out, and head high. He looks down on those beneath him.

In contrast, the young flirty girl, (right), stands with her hands on her hips, tosses her head to swing her pony tail, thrusts her chest out, and smiles as she sways from side to side.

Once you've found your key gesture(s) for each character practice them. Either use a mirror or video yourself. Watch that you go cleanly, without fuss, from one character to another.

Adding mood and voice to character

With the characters established you are ready to add mood and voice.

At the beginning these exercises we focused on understanding and learning the appropriate body language for differing emotions. Now we're going to add that to what you've been working on to establish character.

While holding your key character gesture, add an emotional state.

For example, what would the flirty girl do with her body to show anger, happiness, or sadness?

You'll need to experiment until you find what feels, and looks right. Once you have got it, add voice.

Applying your characterizations to a story

Anything that is direct dialogue, (something someone says to another character), gets the full treatment - that is the appropriate body language and voice for their character.

That means if you've got a salesman talking you become him. You also become the customer, the bystander, or anybody else in your story.

You play all the characters, including yourself, the narrator, linking all the players together.

(As the narrator you stop acting and assume your normal speaking pose and voice.)

Just one more tip to slip into your...

Characterization techniques kit

Using illusion

Because you are playing two or more

people as part of your story doesn't mean you need to rush all over the

stage from one speaking place to another to show who is talking.

You can achieve this through illusion. For each character establish a place they look to whenever they speak or react.

For example, the salesman looks straight ahead. The girl looks up to her right and the boy looks to his left.

The audience will very quickly understand what you're doing and follow without confusion providing your transitions between characters (including narrator) are crisp and clean.

As with most things, practice makes perfect. These characterization techniques will add vibrancy and life to your stories. I hope you enjoy the process of getting better and better at telling them. ☺

Related pages:

- Check these for more specific help with vocal variety, varying your speech rate, using pauses effectively, and breathing effectively.

- For integrating your story into your speech see this page on storytelling set ups.

- For more on body language in public speaking - tips and exercises to support your speech effectively

About the Author: Susan Dugdale, founder of write-out-loud.com, is a qualified teacher of English and drama with over 40 years of experience. Drawing on her professional expertise and her personal journey from shyness to confidence, Susan creates practical, real-world resources to help people find their voice and speak with power.